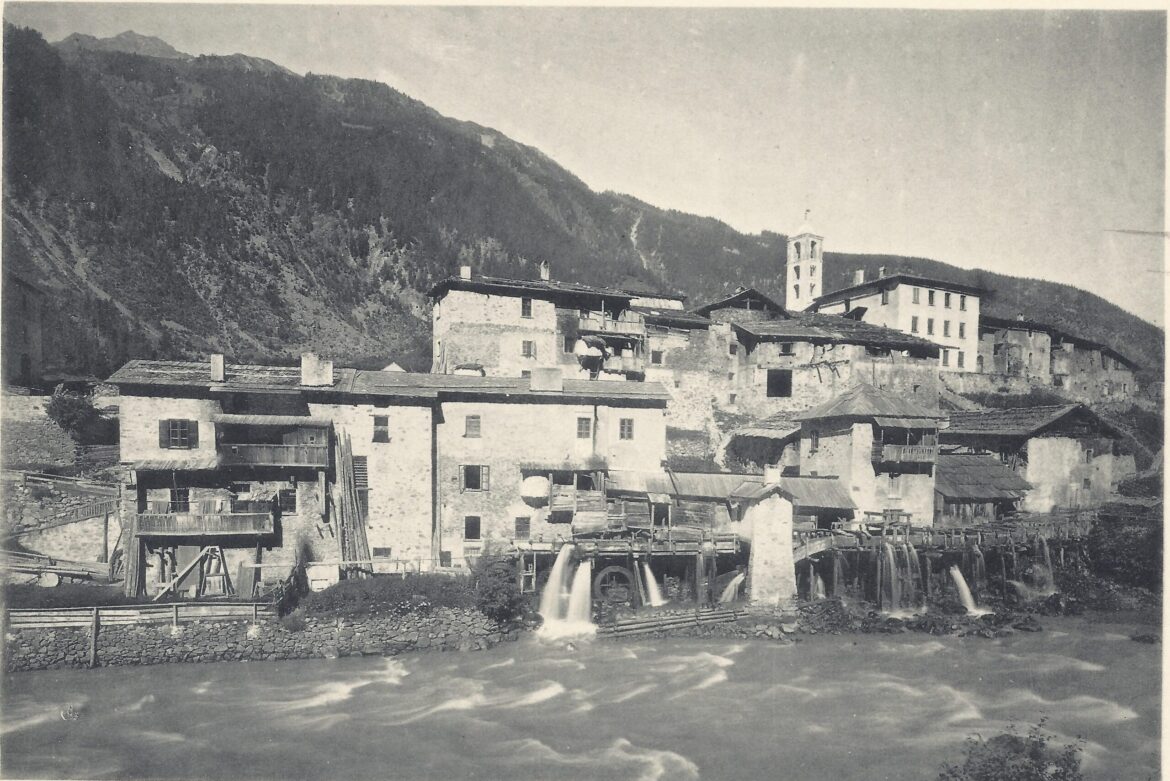

Cepina was home to numerous mills powered by the waters of the Adda River, which ran almost parallel to the various hamlets of the village. In particular, the downstream area of the locality *Bràch* was known for the presence of many of these structures that operated with water channeled through a ditch called *agualar, partly dug into the ground and partly (the terminal section) built with larch wood planks covered in iron (i scosòir). According to a 1844 survey, the conduit measured 315 meters in length, 2.50 meters in width, and 0.60 meters in depth, while the banks were 130 meters long. The water, carried by a wooden beam structure, fell onto the large wheels which, by turning, set various machinery in motion: the press to obtain oil from flax seeds, the hydraulic hammer with the bellows for metalworking (the iron for the artistic gates of the Ossuary was worked here), and the grindstone for sharpening tools. Additionally, the mill’s shaft operated the fulling mill for cloth and the barley huller. In more recent years, there was also a sawmill. The mills in the locality of the same name were three and belonged continuously for centuries to the descendants of the Tyrolean Cristoforo Walzer, who emigrated to Cepina in the second half of the 1700s. In fact, in 1926, Lia Valzer was still listed as the owner of two mills (one operational and one closed), while a third had been sold to the De Gasperi family. That year, the small hamlet was swept away by an avalanche: it detached from Mount Boer and descended right on the hamlet of **Mulìn, causing the formation of a lake whose subsequent flooding completely washed away the mills along with the stored grains, four houses with all their furniture, the power station that supplied the village, the sawmill, and a woodworking machine. The owners quickly re-dug the **agualar* by hand, repaired the buildings, and restored what remained of the equipment that survived the destruction. The sawmill ceased operations around the mid-1950s, while the mills remained operational for another decade; the abandonment of rye cultivation was decisive in determining their fate. At the Valzer house, descendants of the ancient mill owners, some grindstones, and wooden parts that powered the mills are still visible. Part of the equipment has been donated by the owners to the Museo Vallivo di Valfurva, where they are still on display.